Discipline-Based vs. Interdisciplinary Education: It all started with Socrates!

You may be surprised to know that interdisciplinary planning and learning is not new. In fact, it began more than 2 500 years ago with the great Greek educator Socrates, the same guy who educated Plato, who in turn had as one of his disciples, Aristotle. However, despite the interconnectedness of these three historical figures, it turns out that they approached the teaching of disciplines differently: Socrates and Aristotle tended to integrate them, whilst Plato separated them. However, all three included music, dance and gymnastics as essential elements in the study of each of the rest of the disciplines.

Okay, that doesn’t help much. Let’s move on in history and find out some more facts about the interdisciplinary education:

- At the end of the 1800s-early part of the 1900s, John Dewey reactivated integrated learning in the northern American continent, as a backlash from the teacher-centred, rote, divided learning introduced in the latter part of the 18th century by the Prussian king Frederick II, and then continued during the Second Industrial Revolution.

- Shortly afterwards, deeply disturbed by the lack of critical thinking still prevalent in the majority of schools in the United States, Benjamin Bloom developed his three domains of critical thinking to encourage teachers to blend disciplines and so broaden higher-order thinking opportunities for students.

- From the 1960s onwards, Hilda Taba brought renewed attention to the practice of integrated projects through her recommendations for curriculum reforms.

- Today, as a response to the resurgence of standardised assessments, educators such as Heidi Hayes Taylor and researchers such as David Ackerman and D.N. Perkins have furthered the importance of learning through interdisciplinary studies.

Now you’ve learned how to impress your friends, let’s go on.

In our daily lives, do we learn in segmented or integrated ways?

Well, let’s take the following, ostensibly innocent, scene as our starting point:

A 5-year-old child falls in the playground and goes to the school nurse to have her hand bandaged. While she is there, the nurse tells her that eight of her fingers don’t need any care and asks how many need bandaging. The girl thinks carefully and answers ‘two’. The nurse explains that he needs to clean the two fingers, shows the girl the steriliser he is going to put on them, asks her to repeat the word ‘steriliser’, and then explains that this is to help her body fight off any unhealthy cells that would make her feel uncomfortable later on. He adds that in the past (and today) people used honey to do this. He shows her pictures of people in Ancient Egypt bandaging wounds, the plastic ones they use today, and asks her to choose a colour and the images she would like to put on her fingers. The nurse asks the girl to explain what was happening when she fell, how she feels about what’s happened, where her friends think she went, and what she’s going to do next. The girl leaves the nurse’s office and returns to the playground.

During this 15-minute conversation, the nurse integrated the following disciplines and skills: Maths, Science, History, Art, English, sequencing, colours, interpersonal skills, critical thinking, reflection, and inferring.

Wow! Does this happen all the time? Actually, yes it does! Granted, not all daily events are so densely rich in opportunity, but this scene serves to show how our natural way of learning is in a very integrated manner, not divided up into 50 minutes of Maths, 50 minutes of History, 50 minutes of English, 50 minutes of Art, but it can be done – and done more beneficially – through interdisciplinary learning opportunities.

Integrated Studies Foster Skills for Global Interaction

Being fluent in more than one language is not the only criteria for being a more valuable and valued world citizen. Today’s global environment is centred on the development and exchange of knowledge and information. In this light, people will prosper who are fluent not just in languages, but in a variety of disciplines as well. Creativity, adaptability, critical reasoning and collaboration are part of today’s top employability skills, and these are fostered in interdisciplinary projects. They help students to develop multifaceted expertise and grasp the diversity of information and complex associations present in most global interactions.

Some of the most powerful and positive educational outcomes that come out of learning through integrated projects are:

- Increased understanding, retention, and application of general concepts.

- Better overall comprehension of global interdependencies, along with the development of multiple perspectives and points of view, as well as values.

- Increased ability to make decisions, think critically and creatively, and synthesize knowledge beyond the disciplines.

- Enhanced ability to identify, assess, and transfer significant information needed for solving novel problems.

- Promotion of cooperative learning and a better attitude toward oneself as a learner and as a meaningful member of a community.

- Increased motivation.

What are some examples of Interdisciplinary Projects?

So glad you asked! Here are three projects that flesh out different concepts in creative and diverse ways. See what you think. Feel free to use them, adapt them, augment them, but most of all, feel free to let them inspire you to make your own interdisciplinary projects, and share them with your co-workers.

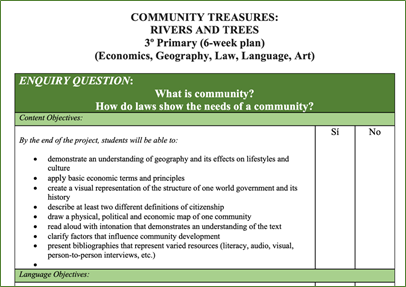

INTERDISCIPLINARY PROJECT 1 - LOWER PRIMARY