We live in a world that has become incredibly multicultural due to migration, technology, educational initiatives, and other factors. The effects of this multiculturalism are both overt and hidden and sometimes even difficult to cope with. To help our students to be able to function effectively in this globalised environment, as educators we need to encourage our students to expand their tolerance for diversity, to think critically about basic and more sophisticated political issues, and to dare to explore human rights that surpass borders. But how?

Having a range of language skills and an awareness of other cultures is becoming increasingly important in our global world. It is important to support bi- and multilingualism and to endorse projects that cross borders in different ways.

Swedish Cultural Foundation

HundrED Spotlight Report

September 2020

Bilingualism is not enough

Most of us are already convinced that bilingual education is a game-changer for our students. From a biological standpoint, studies show how learning through more than one language affects the brain in profound and long-term ways (The Bilingual Advantage, 2021), whilst from a social and professional perspective, being able to express oneself in more than one language is not only enriching, but profitable.

But as language teachers, we’re living in a tricky and particularly challenging time in history. Most of us recognise that it is not only a disservice, but it is not wholly possible, to learn a language without a cultural context. Language is too closely tied to social cues and meaning to be able to be learnt without an understanding of the majority or targeted culture.

However, the goal of bilingualism in all its layers – being able to interpret verbal, corporal, and emotional communication to negotiate meaning – is not enough. We need to include a broader perspective in our curriculum to be able to look ourselves in the mirror and know that we’ve done our best for our students. Why is this so?

The global quarantine has created paradigm shifts in perception

We’re only just beginning to understand the how the global COVID-19 crisis, which began in the early months of 2020, affected us and our societies. One emergent phenomenon was a diametrically opposed dynamic: isolation and connection. The majority of the human population was suddenly and disconcertedly relegated to its homes, becoming at the same time more physically isolated and more digitally connected than ever before.

We were forced to take our classes online, yet many of us had only dabbled in technology. We resisted more familiarity with real time video communication in the hope that it would somehow go away. In fact, what actually happened was that in one global blink we opened our eyes to a dawn in which almost our only means of communicating with family outside our homes, staying informed of events, receiving aid, buying essentials (and non-essentials), maintaining a semblance of continuing education, and reaching out and seeing how people were coping all over the world were via the internet. The world for us had simultaneously come to a standstill and had become incessantly fluid, at the same time.

How is all of this relevant to the classroom? Before Lockdown most of us were only peripherally aware of how intertwined and blended the world had become. With more time spent exclusively on the internet, however, it became clear that our physical separation is only an illusion. In the past two decades, we have leapt at an exponential rate to become a living, breathing beehive of multicultural living, and this has much more serious implications - on many critical levels - than purely technological.

Why should educators be concerned with multiculturalism?

The fact is societies with single, unitary cultures are becoming rare and are being replaced by others in which multiple cultures coexist. It has been estimated that the number of international migrants in the world currently stands at 272 million (UN DESA, 2019). However, minority cultures do not always take part in majority politics and members of minority cultures often have their rights denied by the society at large. This can involve not only citizenship rights, but also rights pertaining to more immediate concerns, such as dignified living spaces, access to adequate healthcare, appropriate nutrition, free education, and, later on, equal access to the job market.

This is where we as educator can make an important difference. By engaging our students with these issues as they manifest themselves in the country, city and town we live in, and even in our schools, we can empower them to lever change.

Our students need to know the differing circumstances of millions of children their age around the world. In fact, it is their right to know that there are:

- 31 million child migrants in the world;

- 13 million child refugees in temporary camps;

- 17 million children who have been forcibly displaced from their countries;

- Almost 100,000 asylum-seeking children still waiting for relief from their critical situations (IOM, 2020).

By knowing about these and other issues (a great tool to help them find out more about this kind of statistic is Diversity Atlas, which measures types and extents of cultural traits in an organisation or school community), our students will be on the right path to becoming knowledgeable participants and negotiators in problem-solving human rights issues, now and in the future.

Our classrooms as a reflection of tolerance exhibited in our communities

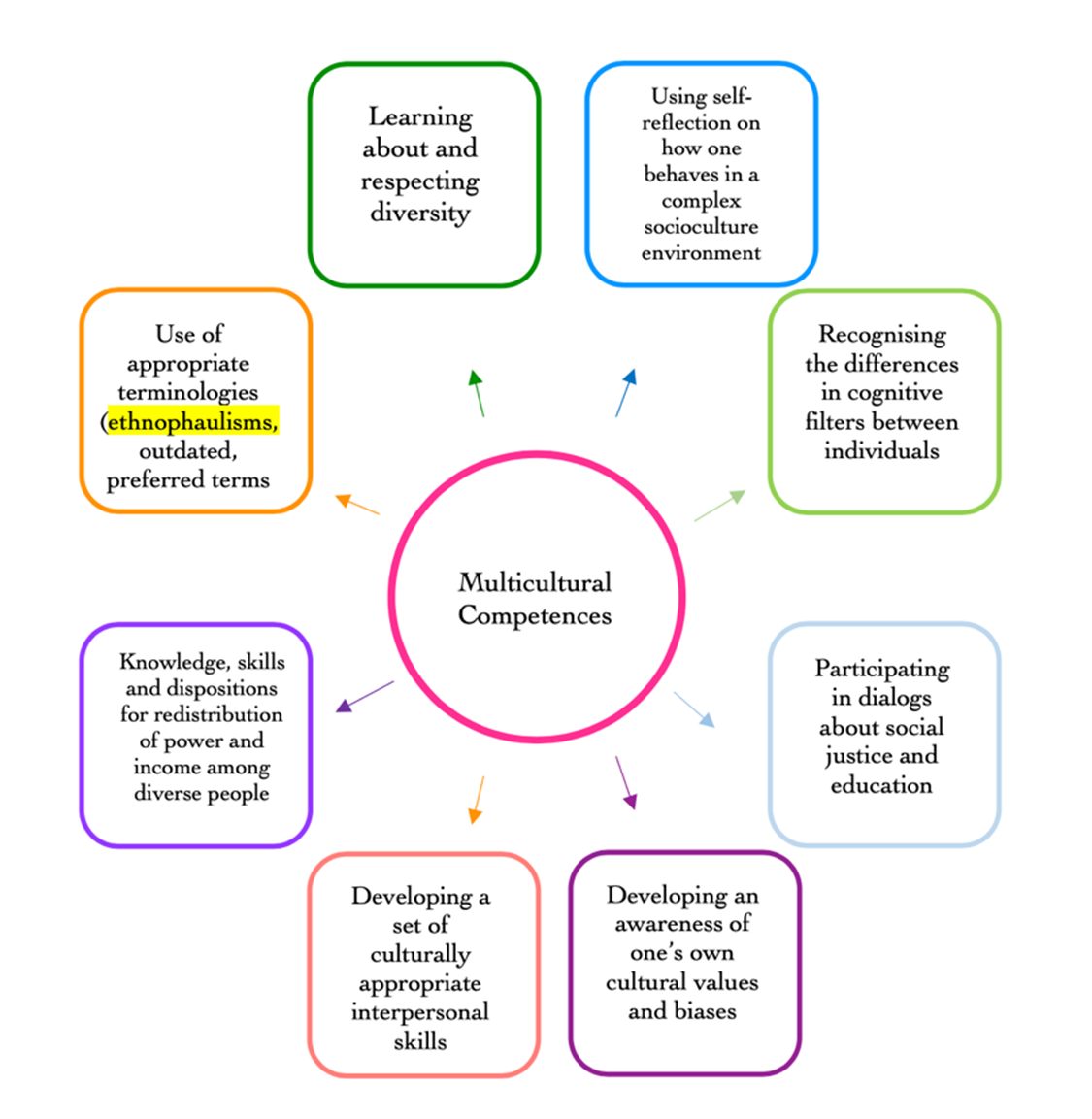

We need to give our students divergent perspectives on these issues. In a world in which they can now easily cross physical and digital borders, we need to help them to become conscious of other cultural perspectives as a foundation of informed cross-cultural interaction by including multicultural competences in our teaching.

Quick question: How many of the following multicultural competences do you, or can you, include in your lessons?